This article discusses the miraculous process of caterpillars turning into butterflies, known as metamorphosis. Rabbi Samuel Waldman, a religious teacher from Brooklyn, describes this process as one of the most evident miracles of Hashem, noting that similar transformations occur in over 60% of all insect species.

In this article we will concentrate on a few more facts about the caterpillar. Firstly, about its eating habit. The caterpillar DOES NOT STOP EATING its special type of leaves for about two weeks straight! The only time they stop eating is when they prepare and then go through their molting stage which is about a 12-hour period. They molt 4 times before they molt into a chrysalis/butterfly. (We will have a full article about the miraculous molting process.) The weight of the caterpillar from when it hatched until its ready to turn into a chrysalis increases close to 3000 times its original weight. (Think of a 6-pound baby. It would have turned into a 18,000-pound gorilla baby in two weeks!) No other creature on earth matches this fantastic rate of growth in such a short period of time!

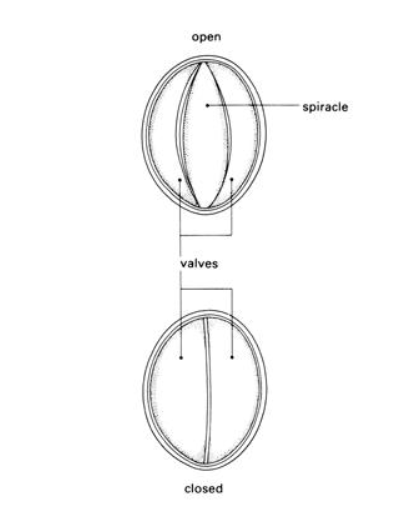

For the rest of this article, we will discuss the amazing breathing/ gas exchange process of the Monarch Butterfly. This process is actually found in most types of insects. Now, basically all insects have an outer skeleton called the exoskeleton. It’s made out of chitin, which is the same material that our fingernails are made of. It’s a hard substance and air can’t really go through it. Therefore, Hashem made that on the outside of the body of the caterpillar (and the butterfly) lying flat with the surface of the outer wall/skin/exoskeleton of the caterpillar there are holes called spiracles. Spiracles are openings that let in the air from the outside. There are typically one pair of spiracles, one on the right side and one on the left side for just about every separate part of the body. So, usually there’s 8 – 10 spiracles on its body. There are special muscles that can open the spiracle and another set of muscles to close them. Some spiracles just have opening muscles and otherwise, when those muscles aren’t working, the spiracles automatically close and remain closed without any muscles. In some insects, instead of muscles to open and close the spiracle, there’s a valve at the end of the atrium that can be opened and closed. (see the picture) The reason to want to stop air flow is to reduce the amount of moisture evaporating out of the trachea system. (We will explain why that’s important soon.)

The black circles are spiracles.

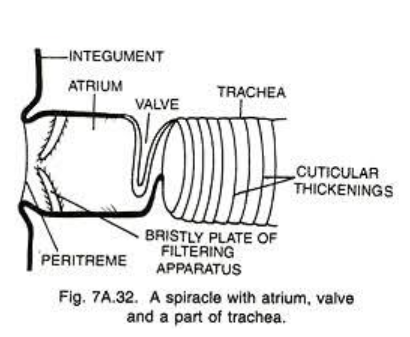

In this picture, all the way to the left is the spiracle. Then comes the atrium. (Integument is a fancy word for the outside skin. Peritreme is the rim/cuticle around the spiracle.) Notice the bristly plate that will filter out any dirt from the air (and there are also a lot of hairs, not shown in this picture, that do a lot of filtering as well.) Then in some insects there’s the valve that controls the air flow, instead of the muscles that control the opening and closing of the actual spiracle piece. After the air goes through the filtering process it will enter the trachea. The trachea are the tubes that air goes in and out of. Going in is the air with oxygen and going out is the carbon dioxide from all the cell activity that the insect does.

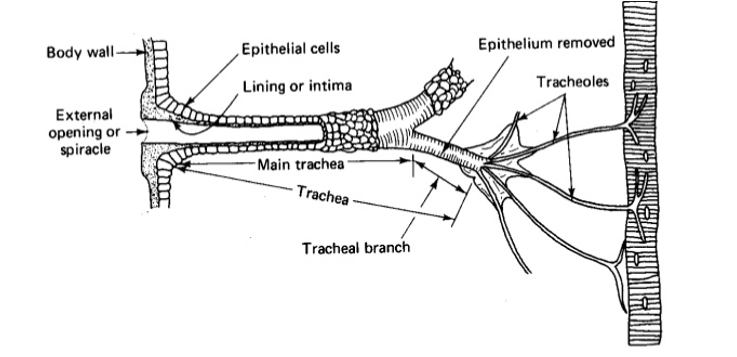

This picture shows the whole process. The air enters at the left through the spiracle. Then it goes down the trachea. From the trachea it branches down to the tracheoles. At the end of each tracheole there’s a special cell that has vital moisture in it, and that cell connects to, and sometimes actually enters, the many, many, cells that need the oxygen. The oxygen that is in the air in the tracheole dissolves into the moisture that’s on the bottom of it, in that special cell, and then through a process called diffusion (a certain chemical process) the oxygen is able to diffuse out of the moisture liquid, into the nearby cells, providing them with the oxygen needed for their survival. At the same time, the carbon dioxide waste that the cells need to get rid of, are diffused the opposite way, by first dissolving from their cell into the moisture of the special cell of the end of the tracheole, and then through diffusion, it gets into to the trachea, and then out through the spiracle. That’s the breathing gas exchange that happens in insects. Because of the extreme importance of there being enough moisture on the bottom of the tracheoles for the gas exchange to take place, that’s why the spiracles need the ability to close, and stay close until there builds up a real need for more oxygen. That’s, so it can keep in the moisture and keep it from drying out.

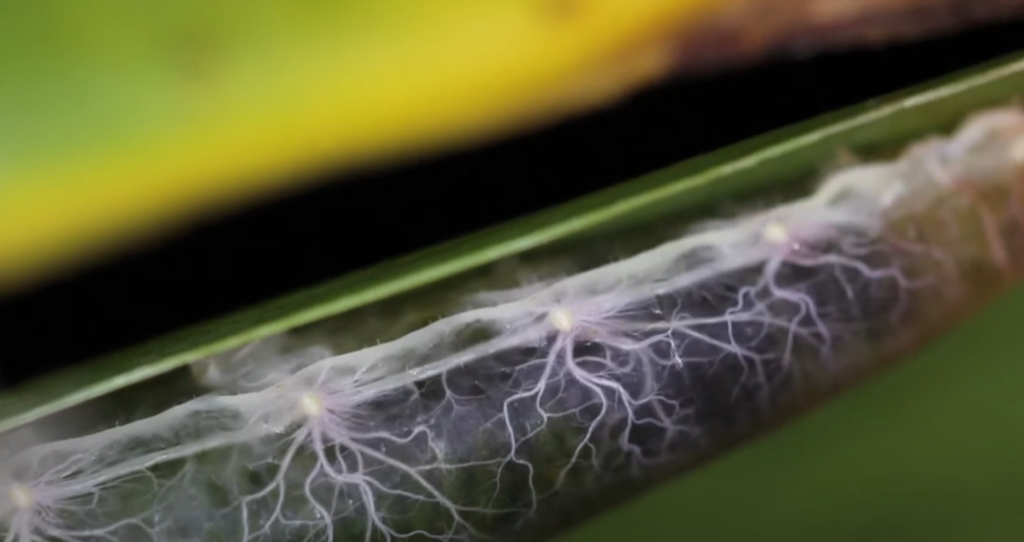

This is a picture a see-through caterpillar! The bright small circles are the spiracles. The white “roots” coming out of the spiracles are the trachea, and impossible to see are the tracheole branching out from the trachea, since they are extremely thin as they branch out of the trachea branches.

Going around the tubes of the trachea are spirals, of something called taenidium. It’s similar to a drier hose that has the metal rings attached to them, going around it, to make sure the walls don’t collapse. The trachea have such similar features. It has these taenidium that keep the tubes open. Many insects also have an air sacs ballooning out of the trachea at some points. This can only take place at places where there’s no taenidium surrounding the trachea. The taenidium are purposely missing at certain areas, so that the trachea tube is expandable at that point and thereby the tube can expand into a sac. It’s needed for times when back up air is needed. It’s more typical to find them in very active insects and surely in flying insects.

One more point about the tracheole. They branch out all over the body, similar to the way capillaries branch out all over human bodies, reaching to all the cells of the insect. So, how wide to you think the tracheole are? Well, what’s the size of a micron? (The symbol of a micron is µm.) A micron is 1/25,400 of one inch! Yes, you read that correctly. Well, the trachea can keep branching out into thinner and thinner tubes until they are a bare 2 microns thick!! And the tracheole branch out of that and are as thin as ONE MICRON, and the tippy tip end of each tracheole is one tenth of one micron thick!!

Hashem very often works in super tiny micro sizes!

So, obviously, this process, step by step, tube by tube, has amazing planning and machinery involved to work out such an amazing breathing process for insects! How great are Your works Hashem! IY”H next week we will see the amazing molting process that takes place in every single insect in the world.

Rabbi Samuel Waldman marvels at the wonders of Hashem’s creation, noting the miraculous aspects of this process and promises future articles to explore the butterfly’s wings and migration, further revealing the intricate and wondrous design of nature.

Read the Part 1 of this article here.